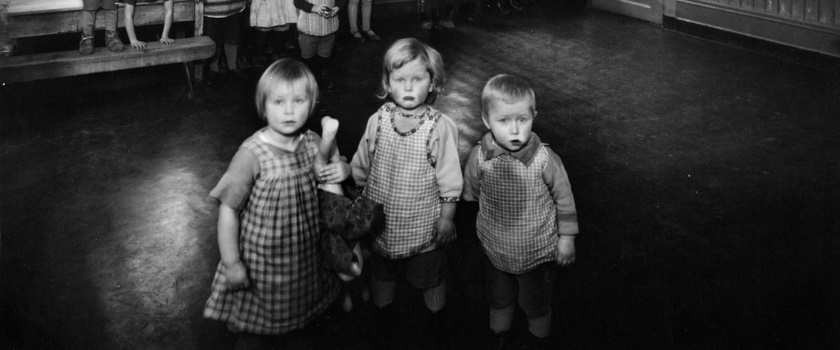

Photo: Labour movement archives and library.

The Castbergian Child Laws

«I believe that if the Odelsting follows through on this it will have done a fine thing, and the day the decision is made will be a day of honour day in this assembly’s history.»

With those words, on 28 January 1915, Johan Castberg concluded his main remarks during the Odelsting’s debate on proposed child laws. At the time Castberg was President of the Odelsting, then one of two chambers that made up the Storting, Norway’s parliament. Castberg was also head of the justice committee. He had been active on the issue since before his election to the Storting in 1900.

The year 2015 was the centennial of the Storting’s passage of the Castbergian Child Laws. These laws gave children born outside of marriage rights to inheritance and to bear their father’s surname. The laws also ensured financial support for unmarried mothers by expanding the maintenance obligation. If a mother failed to receive child support from her child’s father, the municipality was to provide financial assistance.

The child laws strengthened legal protections for children. Norway was among the first countries to introduce such legislation, thus becoming a leader in the field of children’s law.

Johan Castberg. Photo: Storting Archives.

Father of the child laws

The laws were named for Johan Castberg, who entered the Storting as a member of the Liberal Party in 1900. He belonged to the party’s radical wing until 1906, when he became head of the Labour Democrats.

Castberg’s political orientation was distinctly social at a time when social affairs were rising onto the political agenda. Throughout his political life, he was a proponent of women’s and children’s rights and of bringing social differences into balance.

His work on behalf of unmarried mothers and their children began early. From 1901 to 1915 Castberg repeatedly raised the issue of so-called “illegitimate” children and their living conditions.

As Minister of Justice in the first government of Prime Minister Gunnar Knudsen, a fellow Liberal, Castberg had new laws enacted on labour protection, labour oversight and sickness benefits. On his appointment in 1913 to serve as Norway’s first minister of social affairs, Castberg proposed new acts to benefit children that in 1915 would result in passage of the child laws that bear his name.

Katti Anker Møller. Photo: Norwegian Museum of Cultural History.

Mother of the child laws

Johan Castberg’s sister-in-law, Katti Anker Møller, was as important to the legislative process as the minister himself. She was a prominent advocate of women’s issues who, in the early 1900s, travelled the country delivering speeches and taking part in mass meetings.

During the Odelsting debate in January 1915, Castberg’s successor as social affairs minister, Kristian Friis-Pedersen (Liberal Party), highlighted the important role of women:

“Naturally, now that all parties seem to be in agreement to bring about legal provisions that ensure greater maintenance support for the mothers and more care for the children, we feel satisfaction. But we must immediately and clearly acknowledge that this change in general opinion has come about after years of struggle, and that more than anyone else it is the women, with their ever stronger demands for greater legal justice, who have been the driving force in this movement.”

A central figure among the women was Katti Anker Møller. She had worked to promote new legislation since 1901, when she published her first article, “Unmarried Mothers”, in the Norwegian women’s rights journal Nylænde.

Castberg’s early proposals

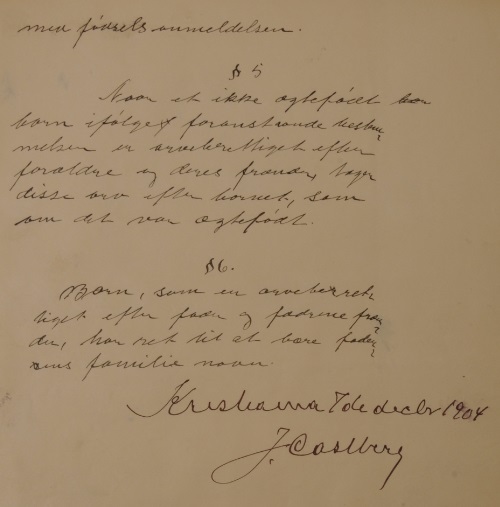

Proposed amendments to the inheritance act as penned by Storting member Castberg, 1904/1905. Photo: Storting Archives.

In 1892 a new act was passed concerning maintenance payments for children born outside of marriage. The fathers’ duty to pay support was somewhat heightened, but enforcement of the law was still left to the unmarried mothers. They themselves had to submit maintenance claims. In practice the changes stemming from the 1892 act were minor, but it is nevertheless considered the forerunner of the Castbergian Child Laws.

The year after his election to the Storting, Johan Castberg put forward a proposal on behalf of De forenede norske arbeidersamfunn, a moderate labour association. The proposal entailed both an expanded paternal maintenance duty and a child’s right to its paternal name and inheritance, and was sent on to the Government. In 1904 Castberg put forward a similar proposal, but many officials thought the issues concerning children born out of wedlock were so complex that a study was needed before making any revision to the law.

The numbers speak

After a brief debate in the Odelsting, in March 1905, Statistics Norway was assigned to conduct a study of children born outside of marriage. Its report was completed in 1907 and played an important part in the subsequent legislative process.

According to the report, most “illegitimate” births in Norway took place in Kristiania (as Oslo was then known), Trondheim and some of the towns farther north. The south and southwest of the country experienced the fewest such births. The most serious finding, however, was that children born outside of marriage had a higher mortality rate than those born inside.

Also apparent was a connection between social class and the occurrence of illegitimate births: “The key fact of the matter, confirmed in the most unambiguous way by the tables, is that the large majority of parents on both the fathers’ and the mothers’ sides are of the working class.”

The entire report may be read here.

From proposal to enactment

In 1909, Justice Minister Castberg proposed a set of child laws on behalf of the Knudsen government. In content, his proposal largely matched the child laws that would come later, but due to a change of government in 1909 the matter was not taken up. Castberg reprised the issue in 1910, along with fellow Liberal Hans Konrad Foosnæs. Once again consideration of the proposal was deferred as the new Government needed time to study the matter.

The Bratlie Government (of Conservatives and the Liberal Left) returned to the subject in 1912 with its own bill, put forward by Justice Minister Fredrik Stang (Conservative Party). It contained much of what had been in the previous proposals, but there was a significant difference. It omitted provisions granting children a right to their father’s name and inheritance.

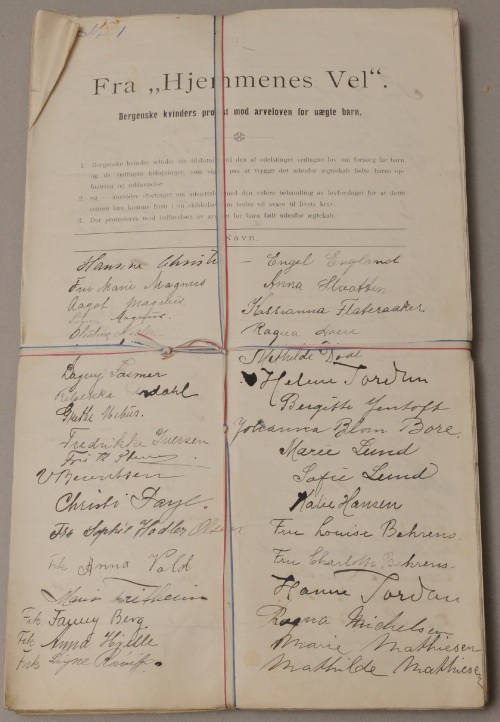

Signature petition from Hjemmenes Vel, a homemakers’ association in Bergen. Photo: Storting Archives.

In 1913, power in the Storting shifted again. In Gunnar Knudsen’s second Government, Castberg was a key force in establishing a ministry dedicated to social issues. He himself became the country’s first social affairs minister and in 1914 put forward a proposal for the preparation of: 1) an act relating to children whose parents have not entered into marriage with each other, 2) an act amending the law on inheritance, 3) an act amending the law on asset disposition between spouses, 4) an act amending the law on recourse to dissolution of marriage, 5) an act relating to parents and children born in wedlock, and 6) an act relating to social assistance for children.

After extensive debate in the Odelsting and in the Storting’s other camber, the Lagting, the Castbergian Child Laws were adopted on 10 April 1915.

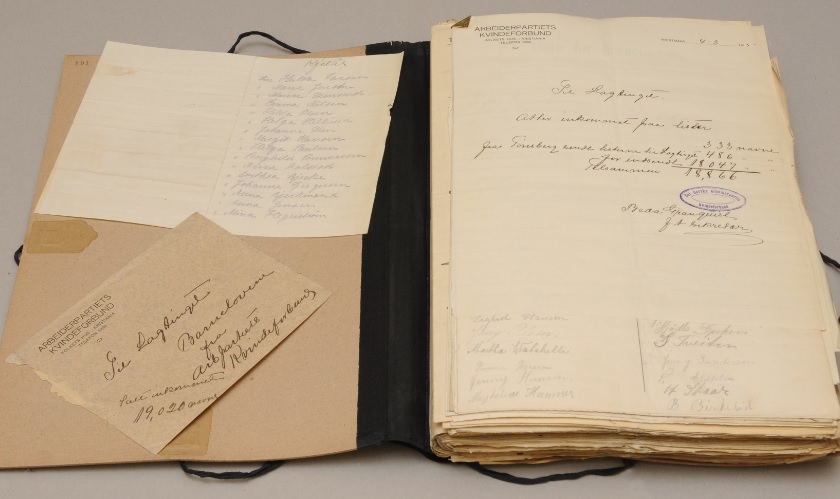

Protests and endorsements

Opposition to the laws was substantial, especially in conservative circles where there was worry about the impact on family, marriage and home. The protests focused largely on the right of inheritance and the right to use the father’s surname.

Working-class women’s associations, in contrast, were concerned about justice for children born outside of marriage and for unmarried mothers who found themselves in difficult straits. These unmarried women most often belonged to the working class. The big economic challenges they faced came on top of the social stigma then associated with giving birth to a so-called illegitimate child.

Signature petition from the Labour Party women’s association. Photo: Storting Archives.

This online presentation was created by the Storting Archives in connection with a seminar on the Castbergian Child Laws on 24 November 2015 in the Lagting chamber.

Last updated: 24.11.2017 10:04